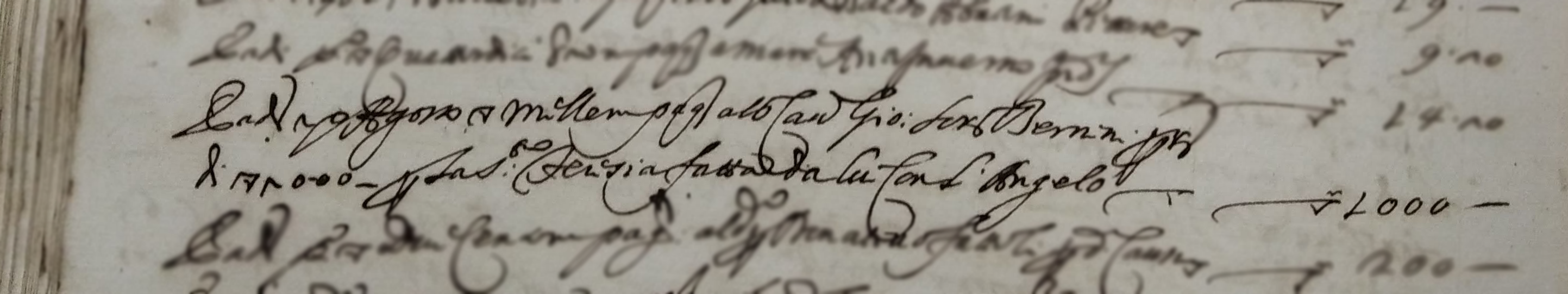

Figure 1. Ledger for 1652, leaf 734.

And on the day of 20 August one thousand scudi paid to Giovan Lorenzo Bernini, Knight, out of 2,000 scudi for the Saint Theresa with the angel made by him 1,000 scudi

Et a di 20 agosto s(cudi) mille m(oneta) pag(ati) al Cav(alier) Gio(van) Lor(enzo) Bernini per / di s(cudi) 2000 p(er) la S(an)ta Teresia fatta da lui con l’Angelo s(cudi) 1000

In the years 1647-52, Gian Lorenzo Bernini created the celebrated Ecstasy of Saint Teresa of Avila for the Cornaro Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. The marble and bronze sculpture portrays the transverberation of the saint. In the language of Christian mysticism, this is the moment when the saint's heart is pierced by an angel with a flaming lance, awakening her love for God. The work was commissioned by Cardinal Federico Cornaro, a refined and well-known Venetian whose wealthy and prestigious family had settled in Rome a few years earlier. The cardinal wanted to have a majestic family chapel built, while this commission was a great opportunity for Bernini to redeem himself in the eyes of Roman society, after his failed project of a bell tower for the façade of St. Peter's.

What's the Ecstasy got to do with a 17th century public bank’s ledger? The history of Bernini's work went hand in hand with the payments made out to him, which were accurately recorded in the account books of Banco di Santo Spirito, a public bank within the then Papal State (we can call it 'Banco' for short). In 1647, Cardinal Cornaro set up a dedicated account with the Banco for building the family chapel, through which all payments were made. The surviving records from the Banco are now owned by UniCredit S.p.A. and are held in Banca d'Italia's Historical Archives thanks to a loan agreement. While these archives from the Banco di Santo Spirito consist almost exclusively of accounting material, they are still a treasure trove of information for researchers (mostly art historians) reconstructing artwork commissions on the thriving Roman market of that time. As far as Cornaro's chapel is concerned, the ledgers have a very interesting story to tell.

Figure 2. two BSS ledgers - @Asbi.

The 'Private banks and public counters. Italy between the 14th and 17th century' section of 'The Adventure of Money' exhibition, had a few of the Banco's ledgers on display, including one (from 1652) recording that 'on 20 August, one thousand scudi were paid to Giovan Lorenzo Bernini, Knight, out of 2,000 scudi for the Saint Theresa and angel made by him (s[cudi] mille m[oneta] pag[ati] al Cav[alier] Gio[van] Lor[enzo] Bernini p[er] / di s[cudi] 2000 p[er] la S[an]ta Teresia fatta da lui con l'Angelo)'.

Bernini's total remuneration for the Ecstasy came to 2,000 scudi. The payment of 1,000 scudi had been preceded by two other payments, 500 scudi each, on 23 June 1649 and 5 January 1652, respectively.

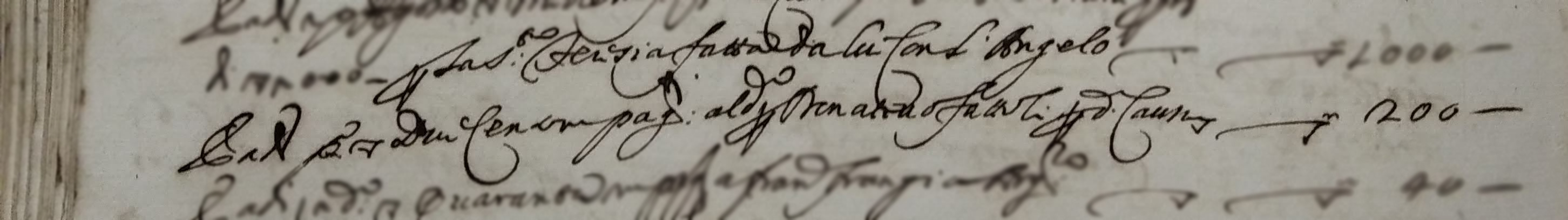

To these must be added another 200 scudi paid to Bernini as a gift ('per donativo fattoli'). In August 1652, the chapel must have been almost completed, given that subsequent payments (the last of which was in 1653) are for the work of installing the sculpture in the chapel. We may suppose this payment was a personal acknowledgement the cardinal made to the maestro for the execution of the Ecstasy.

Figure 3. Ledger for 1652, leaf 734.

And on said [20 August] two hundred scudi paid to said [G. L. Bernini, Knight] as gift made out for said cause

Et a di d(ett)o [20 agosto] s(cudi) Due Cento m(oneta) pag(ati) al d(ett)o [Cavalier G. L. Bernini] per Donativo fattoli p(er) d(etta) Causa [la Santa Teresia] s(cudi) 200

The records from the Banco also give us a picture of the network of labourers who assisted Bernini in making the Ecstasy. The stonemason Gabriele Renzi, for instance, received the not inconsiderable sum of 1,450 scudi in 1647 alone, and substantial payments to Renzi continued until 1652. These amounts were probably for Renzi's work on the chapel's architectural elements, as well as for supplying the precious marbles themselves. Numerous payments for masonry and stucco work were made to master Giovanni Albino, too, between 1648 and 1653. And so on, though to a lesser degree, with other carvers, stonemasons, sculptors, silversmiths, gilders, painters and bronze workers[1]. The fact the sums were paid through a dedicated account also illustrates how the Banco operated in practice. Going around Rome with that kind of cash was far from usual, if not downright risky. Instead, the Banco would issue coupons (see photo) which circulated freely in Rome. These coupons worked along the lines of a cheque: they could be issued by a current account holder within the limits of the sum deposited by them, and could be transferred from one holder to another, subject to the Bank's officials verifying the amount was covered. In this way, the actual circulation of metal coins was practically nil in Rome. As stated in the founding document of the Banco (the brief signed by Pope Paul V), lending was not allowed: it could only receive sums on deposit and return them or transfer amounts from one deposit account to another. Otherwise, the deposited sums could only be used to purchase a form of 'government' securities issued by the Apostolic Chamber of the Papal States.

Figure 4. BSS coupons @Asbi.

In real terms, how much would the 2,000 scudi paid to Bernini have been worth? Even when we leave aside its fluctuating inflation, the cost of living in Rome was broadly much higher at that time than in other European cities[2]. Wheat, for example, cost about 4 baiocchi per kilo, about twice as much as in Naples. Quality fish would cost 24 baiocchi per kilo, which was also the price for two roosters. Meat was cheaper: most meat could be bought for 9 baiocchi per kilo, including lamb; pork was half that amount. Wine, which provided most of a common person's daily calories, alongside bread, cost between three and four baiocchi per litre; one baiocco would buy you a dozen eggs. As for wages, a skilled bricklayer earned 35 baiocchi a day. A doctor serving on a galley, instead, earned 216 scudi a year, whereas the average annual salary for a professor at Rome's university was 166 scudi. It's easy to see that Bernini's 2,000 scudi was a huge payment, equivalent to 2,400,000 eggs or about 22,000 kilos of meat, or about 6,000 working days for a bricklayer or 12 years' salary for a university professor!

[1] C. Napoleone, Bernini e il cantiere della Cappella Cornaro, in «Antologia di Belle Arti», n.s., LV-LVIII, 1998, pp. 172-86.